Which Are Needed To Determine The Equilibrium Of A Good Or Service

fourteen Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium

Learning Objectives

- Employ need and supply to explain how equilibrium price and quantity are determined in a market.

- Understand the concepts of surpluses and shortages and the pressures on toll they generate.

- Explain the impact of a change in demand or supply on equilibrium price and quantity.

- Explain how the circular menstruum model provides an overview of demand and supply in product and factor markets and how the model suggests ways in which these markets are linked.

In this department nosotros combine the demand and supply curves nosotros accept but studied into a new model. The model of demand and supply uses demand and supply curves to explain the determination of price and quantity in a market.

The Decision of Price and Quantity

The logic of the model of need and supply is elementary. The demand curve shows the quantities of a item skilful or service that buyers will be willing and able to purchase at each price during a specified period. The supply curve shows the quantities that sellers will offer for sale at each price during that same period. By putting the ii curves together, we should be able to find a toll at which the quantity buyers are willing and able to buy equals the quantity sellers volition offer for sale.

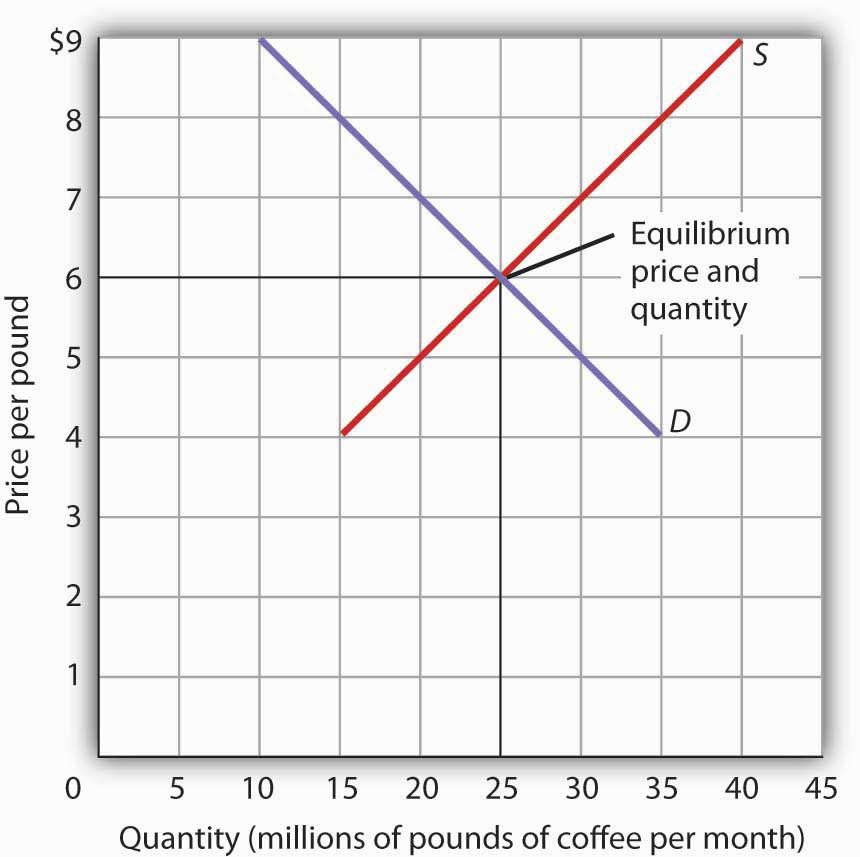

Figure 2.xiv "The Conclusion of Equilibrium Price and Quantity" combines the demand and supply data introduced in Figure 2.1 "A Need Schedule and a Demand Curve" and Figure 2.eight "A Supply Schedule and a Supply Curve" Notice that the two curves intersect at a price of $half-dozen per pound—at this price the quantities demanded and supplied are equal. Buyers want to buy, and sellers are willing to offer for auction, 25 1000000 pounds of coffee per month. The market for coffee is in equilibrium. Unless the need or supply curve shifts, there will be no tendency for price to alter. The equilibrium price in whatsoever market is the price at which quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. The equilibrium price in the market for coffee is thus $six per pound. The equilibrium quantity is the quantity demanded and supplied at the equilibrium price.

Figure 2.fourteen The Determination of Equilibrium Price and Quantity

When we combine the need and supply curves for a good in a single graph, the bespeak at which they intersect identifies the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity. Hither, the equilibrium cost is $6 per pound. Consumers need, and suppliers supply, 25 million pounds of java per month at this price.

With an upwards-sloping supply curve and a down-sloping demand curve, at that place is only a single price at which the two curves intersect. This ways there is only ane price at which equilibrium is achieved. It follows that at any cost other than the equilibrium price, the market will not be in equilibrium. We adjacent examine what happens at prices other than the equilibrium price.

Surpluses

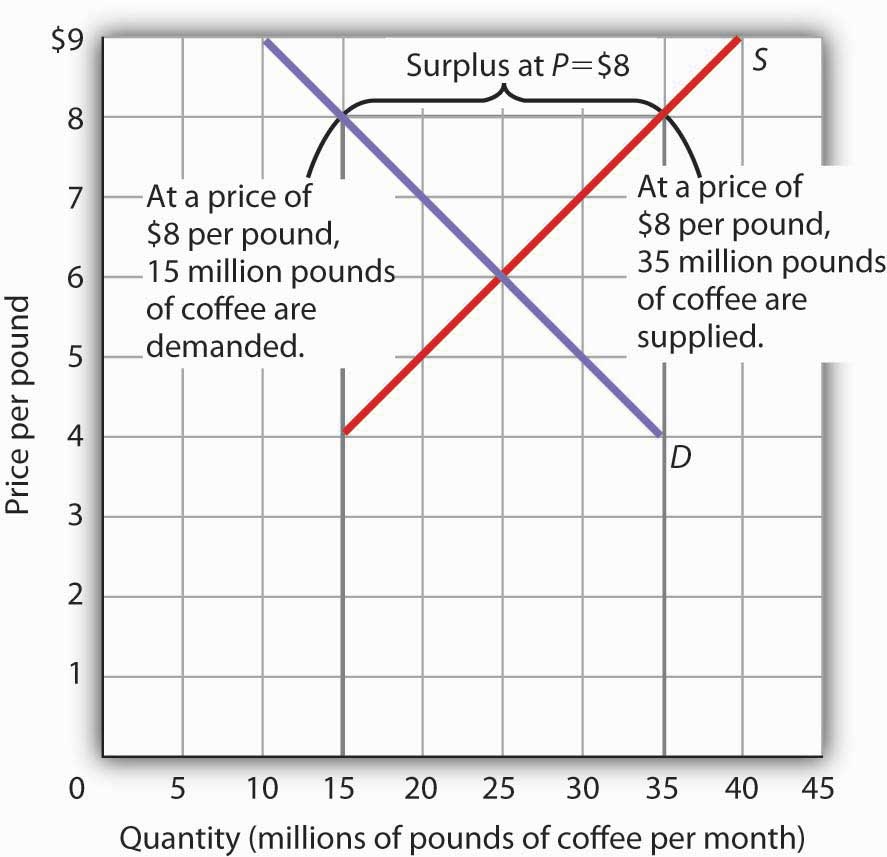

Effigy ii.fifteen "A Surplus in the Market for Coffee" shows the same need and supply curves nosotros have just examined, merely this time the initial price is $8 per pound of java. Because nosotros no longer have a residue between quantity demanded and quantity supplied, this toll is not the equilibrium price. At a price of $viii, nosotros read over to the demand bend to determine the quantity of coffee consumers will be willing to buy—15 million pounds per month. The supply bend tells the states what sellers will offer for sale—35 one thousand thousand pounds per month. The difference, 20 one thousand thousand pounds of coffee per calendar month, is called a surplus. More by and large, a surplus is the amount by which the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the current cost. There is, of form, no surplus at the equilibrium price; a surplus occurs only if the electric current price exceeds the equilibrium price.

Figure two.15 A Surplus in the Market for Coffee

At a price of $8, the quantity supplied is 35 million pounds of coffee per month and the quantity demanded is xv million pounds per month; in that location is a surplus of 20 million pounds of coffee per month. Given a surplus, the price volition autumn quickly toward the equilibrium level of $6.

A surplus in the market place for coffee will not final long. With unsold coffee on the market, sellers volition begin to reduce their prices to clear out unsold coffee. Equally the price of coffee begins to fall, the quantity of java supplied begins to decline. At the same time, the quantity of java demanded begins to rise. Remember that the reduction in quantity supplied is a motility along the supply curve—the curve itself does not shift in response to a reduction in price. Similarly, the increase in quantity demanded is a move along the need bend—the demand curve does not shift in response to a reduction in toll. Price will go along to autumn until it reaches its equilibrium level, at which the need and supply curves intersect. At that point, at that place will be no trend for toll to fall farther. In general, surpluses in the marketplace are short-lived. The prices of most goods and services adapt quickly, eliminating the surplus. Later on, we will discuss some markets in which adjustment of cost to equilibrium may occur but very slowly or not at all.

Shortages

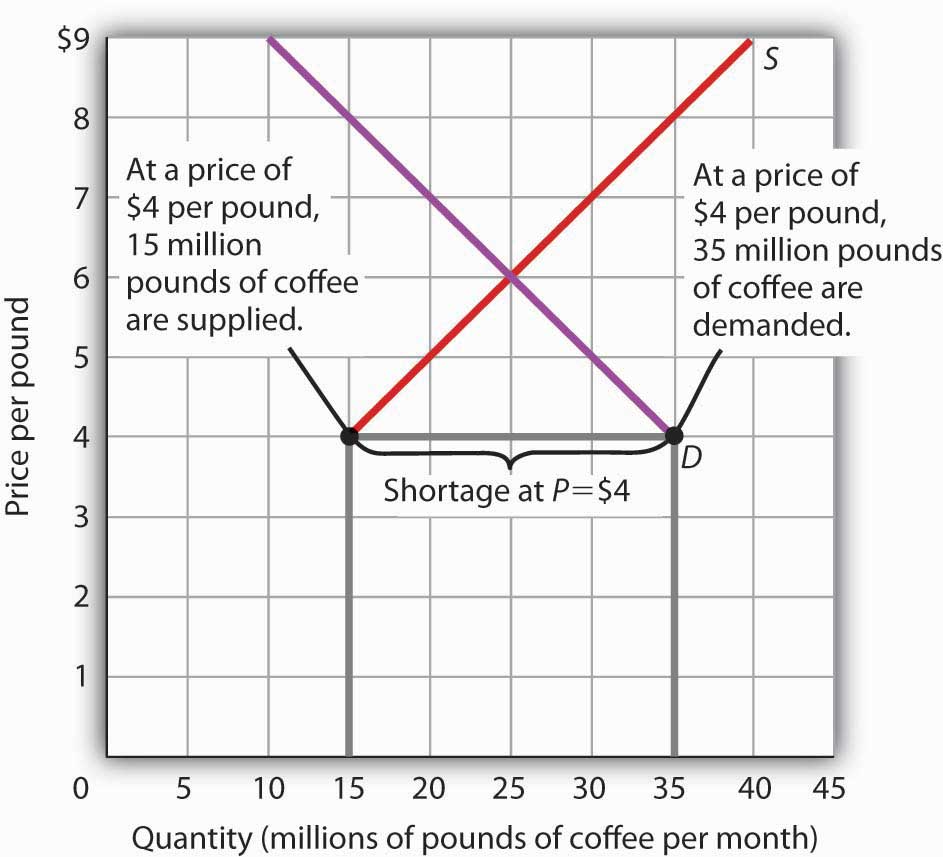

Just as a price above the equilibrium price volition crusade a surplus, a price below equilibrium volition cause a shortage. A shortage is the amount by which the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at the current price.

Figure 2.16 "A Shortage in the Market for Coffee" shows a shortage in the market for coffee. Suppose the toll is $four per pound. At that price, 15 1000000 pounds of coffee would be supplied per month, and 35 million pounds would exist demanded per month. When more than coffee is demanded than supplied, in that location is a shortage.

Figure 2.16 A Shortage in the Market for Coffee

At a cost of $4 per pound, the quantity of java demanded is 35 million pounds per month and the quantity supplied is fifteen 1000000 pounds per month. The consequence is a shortage of xx meg pounds of coffee per month.

In the confront of a shortage, sellers are probable to brainstorm to raise their prices. Equally the cost rises, there will exist an increase in the quantity supplied (but not a change in supply) and a reduction in the quantity demanded (simply not a alter in demand) until the equilibrium toll is achieved.

Shifts in Demand and Supply

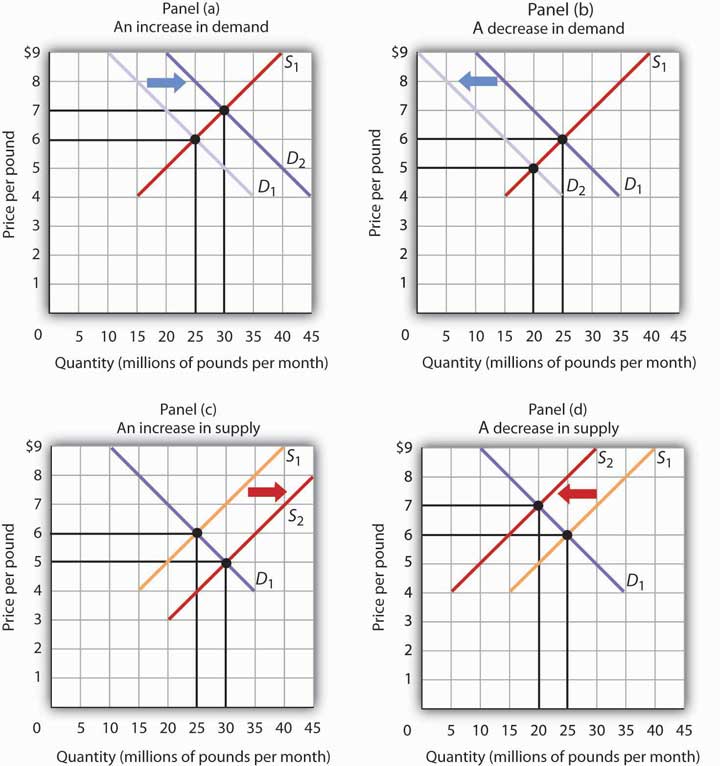

Effigy ii.17 Changes in Need and Supply

A alter in demand or in supply changes the equilibrium solution in the model. Panels (a) and (b) show an increase and a decrease in demand, respectively; Panels (c) and (d) show an increase and a subtract in supply, respectively.

A change in one of the variables (shifters) held abiding in any model of demand and supply will create a change in need or supply. A shift in a demand or supply curve changes the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity for a good or service. Figure ii.17 "Changes in Demand and Supply" combines the information near changes in the demand and supply of java presented in Figure two.two "An Increase in Demand" Figure 2.3 "A Reduction in Demand" Figure two.9 "An Increase in Supply" and Figure ii.ten "A Reduction in Supply" In each case, the original equilibrium price is $six per pound, and the respective equilibrium quantity is 25 one thousand thousand pounds of java per month. Effigy ii.17 "Changes in Demand and Supply" shows what happens with an increase in need, a reduction in need, an increase in supply, and a reduction in supply. Nosotros and then wait at what happens if both curves shift simultaneously. Each of these possibilities is discussed in turn below.

An Increase in Demand

An increase in demand for java shifts the need curve to the right, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 2.17 "Changes in Demand and Supply". The equilibrium cost rises to $7 per pound. Every bit the toll rises to the new equilibrium level, the quantity supplied increases to 30 1000000 pounds of coffee per month. Notice that the supply bend does not shift; rather, in that location is a movement along the supply bend.

Demand shifters that could cause an increase in demand include a shift in preferences that leads to greater coffee consumption; a lower price for a complement to coffee, such as doughnuts; a college price for a substitute for coffee, such as tea; an increment in income; and an increase in population. A change in buyer expectations, perhaps due to predictions of bad atmospheric condition lowering expected yields on coffee plants and increasing hereafter coffee prices, could besides increment current demand.

A Decrease in Demand

Panel (b) of Figure 2.17 "Changes in Need and Supply" shows that a decrease in need shifts the need curve to the left. The equilibrium price falls to $5 per pound. As the toll falls to the new equilibrium level, the quantity supplied decreases to 20 million pounds of coffee per month.

Demand shifters that could reduce the need for coffee include a shift in preferences that makes people want to eat less coffee; an increase in the price of a complement, such as doughnuts; a reduction in the toll of a substitute, such as tea; a reduction in income; a reduction in population; and a alter in heir-apparent expectations that leads people to look lower prices for java in the time to come.

An Increment in Supply

An increase in the supply of coffee shifts the supply bend to the right, as shown in Console (c) of Figure 2.17 "Changes in Demand and Supply". The equilibrium cost falls to $five per pound. As the cost falls to the new equilibrium level, the quantity of coffee demanded increases to 30 million pounds of coffee per calendar month. Discover that the demand curve does non shift; rather, there is movement forth the need bend.

Possible supply shifters that could increment supply include a reduction in the price of an input such equally labor, a reject in the returns available from culling uses of the inputs that produce coffee, an comeback in the technology of coffee production, good weather, and an increase in the number of java-producing firms.

A Decrease in Supply

Panel (d) of Effigy two.17 "Changes in Demand and Supply" shows that a subtract in supply shifts the supply bend to the left. The equilibrium price rises to $seven per pound. Every bit the cost rises to the new equilibrium level, the quantity demanded decreases to 20 million pounds of coffee per month.

Possible supply shifters that could reduce supply include an increase in the prices of inputs used in the production of coffee, an increase in the returns available from culling uses of these inputs, a decline in production because of problems in engineering (peradventure caused by a restriction on pesticides used to protect coffee beans), a reduction in the number of coffee-producing firms, or a natural event, such as excessive pelting.

Heads Up!

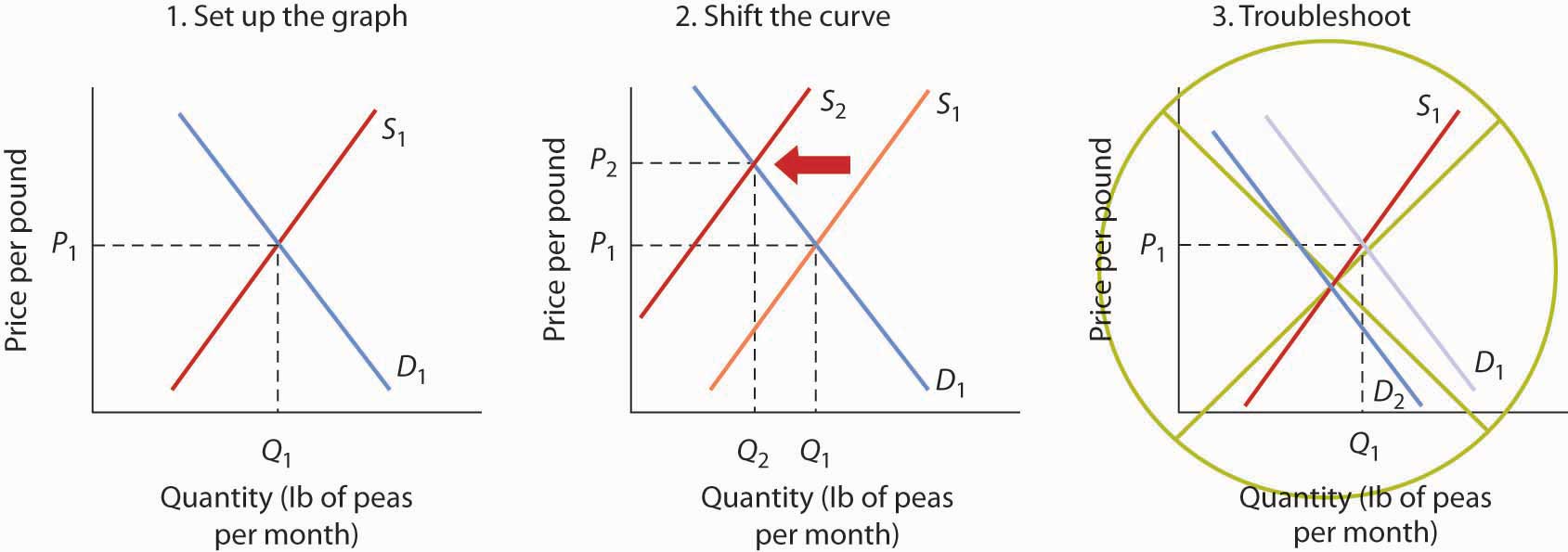

Figure two.18

Y'all are likely to exist given bug in which you lot will have to shift a demand or supply bend.

Suppose you are told that an invasion of pod-crunching insects has gobbled up one-half the ingather of fresh peas, and you lot are asked to use need and supply assay to predict what will happen to the price and quantity of peas demanded and supplied. Hither are some suggestions.

Put the quantity of the good you are asked to analyze on the horizontal axis and its cost on the vertical axis. Draw a downward-sloping line for demand and an upward-sloping line for supply. The initial equilibrium toll is determined past the intersection of the 2 curves. Label the equilibrium solution. You may find it helpful to use a number for the equilibrium price instead of the letter "P." Selection a cost that seems plausible, say, 79¢ per pound. Do not worry about the precise positions of the demand and supply curves; you cannot exist expected to know what they are.

Step 2 can exist the almost hard step; the trouble is to decide which bend to shift. The cardinal is to recollect the departure between a change in demand or supply and a change in quantity demanded or supplied. At each price, inquire yourself whether the given event would modify the quantity demanded. Would the fact that a bug has attacked the pea crop change the quantity demanded at a cost of, say, 79¢ per pound? Clearly not; none of the demand shifters have changed. The event would, yet, reduce the quantity supplied at this price, and the supply curve would shift to the left. At that place is a modify in supply and a reduction in the quantity demanded. There is no modify in demand.

Side by side check to see whether the result you have obtained makes sense. The graph in Step 2 makes sense; it shows cost rising and quantity demanded falling.

It is easy to make a mistake such equally the 1 shown in the third figure of this Heads Up! I might, for example, reason that when fewer peas are available, fewer will exist demanded, and therefore the demand curve volition shift to the left. This suggests the toll of peas will autumn—but that does not make sense. If merely half as many fresh peas were available, their cost would surely rising. The error here lies in confusing a modify in quantity demanded with a change in need. Yes, buyers will end upwardly ownership fewer peas. But no, they will not demand fewer peas at each price than before; the demand curve does not shift.

Simultaneous Shifts

Equally we have seen, when either the demand or the supply curve shifts, the results are unambiguous; that is, we know what will happen to both equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, then long as we know whether demand or supply increased or decreased. Nevertheless, in practice, several events may occur at effectually the same time that cause both the demand and supply curves to shift. To figure out what happens to equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, we must know not only in which management the demand and supply curves have shifted but also the relative corporeality by which each bend shifts. Of course, the demand and supply curves could shift in the same management or in reverse directions, depending on the specific events causing them to shift.

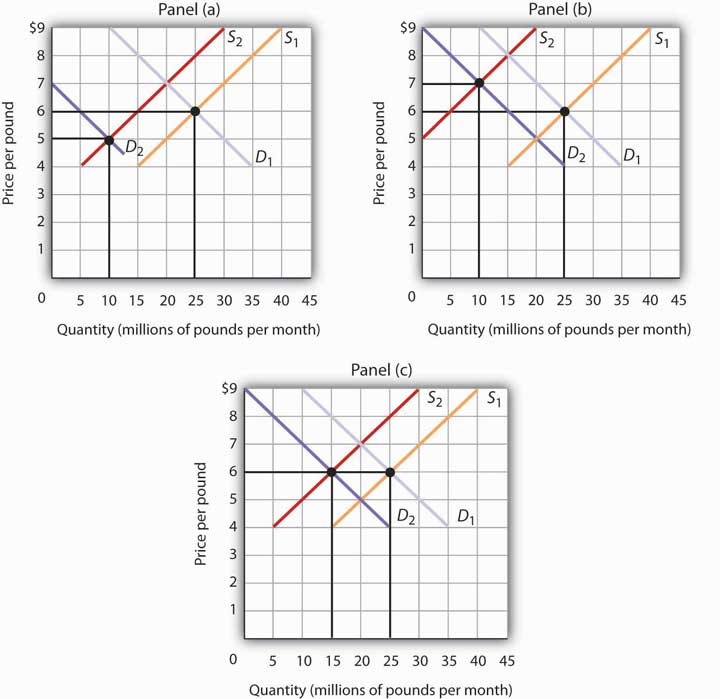

For example, all three panels of Figure 2.nineteen "Simultaneous Decreases in Demand and Supply" testify a decrease in demand for coffee (caused perhaps past a subtract in the price of a substitute practiced, such as tea) and a simultaneous decrease in the supply of coffee (caused mayhap by bad conditions). Since reductions in demand and supply, considered separately, each cause the equilibrium quantity to fall, the impact of both curves shifting simultaneously to the left ways that the new equilibrium quantity of coffee is less than the old equilibrium quantity. The effect on the equilibrium price, though, is cryptic. Whether the equilibrium cost is higher, lower, or unchanged depends on the extent to which each curve shifts.

Figure 2.19 Simultaneous Decreases in Need and Supply

Both the demand and the supply of coffee decrease. Since decreases in demand and supply, considered separately, each cause equilibrium quantity to fall, the affect of both decreasing simultaneously means that a new equilibrium quantity of java must be less than the onetime equilibrium quantity. In Panel (a), the need bend shifts farther to the left than does the supply bend, and then equilibrium price falls. In Panel (b), the supply curve shifts farther to the left than does the demand bend, and so the equilibrium price rises. In Panel (c), both curves shift to the left past the aforementioned corporeality, so equilibrium price stays the same.

If the need curve shifts farther to the left than does the supply curve, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure ii.19 "Simultaneous Decreases in Need and Supply", so the equilibrium toll will be lower than information technology was earlier the curves shifted. In this case the new equilibrium price falls from $6 per pound to $v per pound. If the shift to the left of the supply curve is greater than that of the demand curve, the equilibrium toll will be higher than it was earlier, equally shown in Panel (b). In this case, the new equilibrium price rises to $7 per pound. In Panel (c), since both curves shift to the left by the same amount, equilibrium price does not modify; it remains $six per pound.

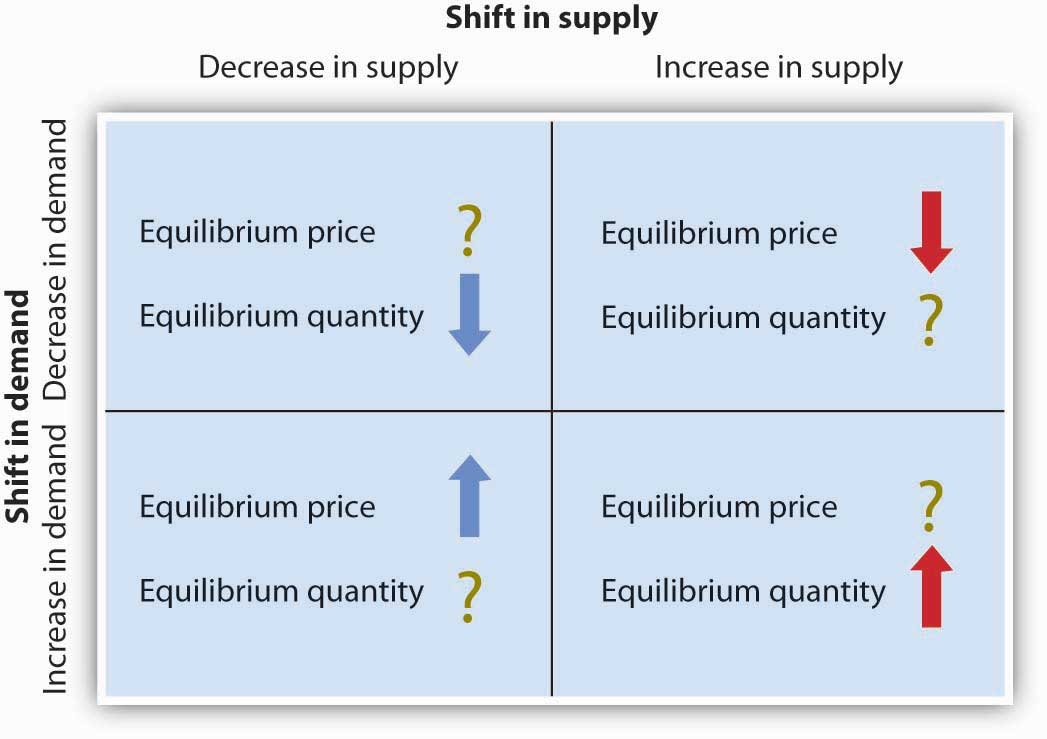

Regardless of the scenario, changes in equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity resulting from two dissimilar events need to be considered separately. If both events crusade equilibrium price or quantity to move in the same direction, then clearly cost or quantity tin be expected to movement in that direction. If i event causes price or quantity to ascent while the other causes it to fall, the extent by which each curve shifts is critical to figuring out what happens. Figure 2.xx "Simultaneous Shifts in Demand and Supply" summarizes what may happen to equilibrium price and quantity when need and supply both shift.

Figure 2.twenty Simultaneous Shifts in Demand and Supply

If simultaneous shifts in demand and supply cause equilibrium price or quantity to motility in the same direction, then equilibrium price or quantity clearly moves in that management. If the shift in one of the curves causes equilibrium price or quantity to rise while the shift in the other curve causes equilibrium price or quantity to autumn, then the relative amount by which each bend shifts is critical to figuring out what happens to that variable.

As demand and supply curves shift, prices suit to maintain a balance between the quantity of a good demanded and the quantity supplied. If prices did not arrange, this balance could not be maintained.

Notice that the demand and supply curves that we have examined in this chapter have all been drawn as linear. This simplification of the real world makes the graphs a chip easier to read without sacrificing the essential point: whether the curves are linear or nonlinear, need curves are downward sloping and supply curves are by and large upward sloping. As circumstances that shift the demand curve or the supply curve modify, we can analyze what volition happen to toll and what will happen to quantity.

An Overview of Demand and Supply: The Round Period Model

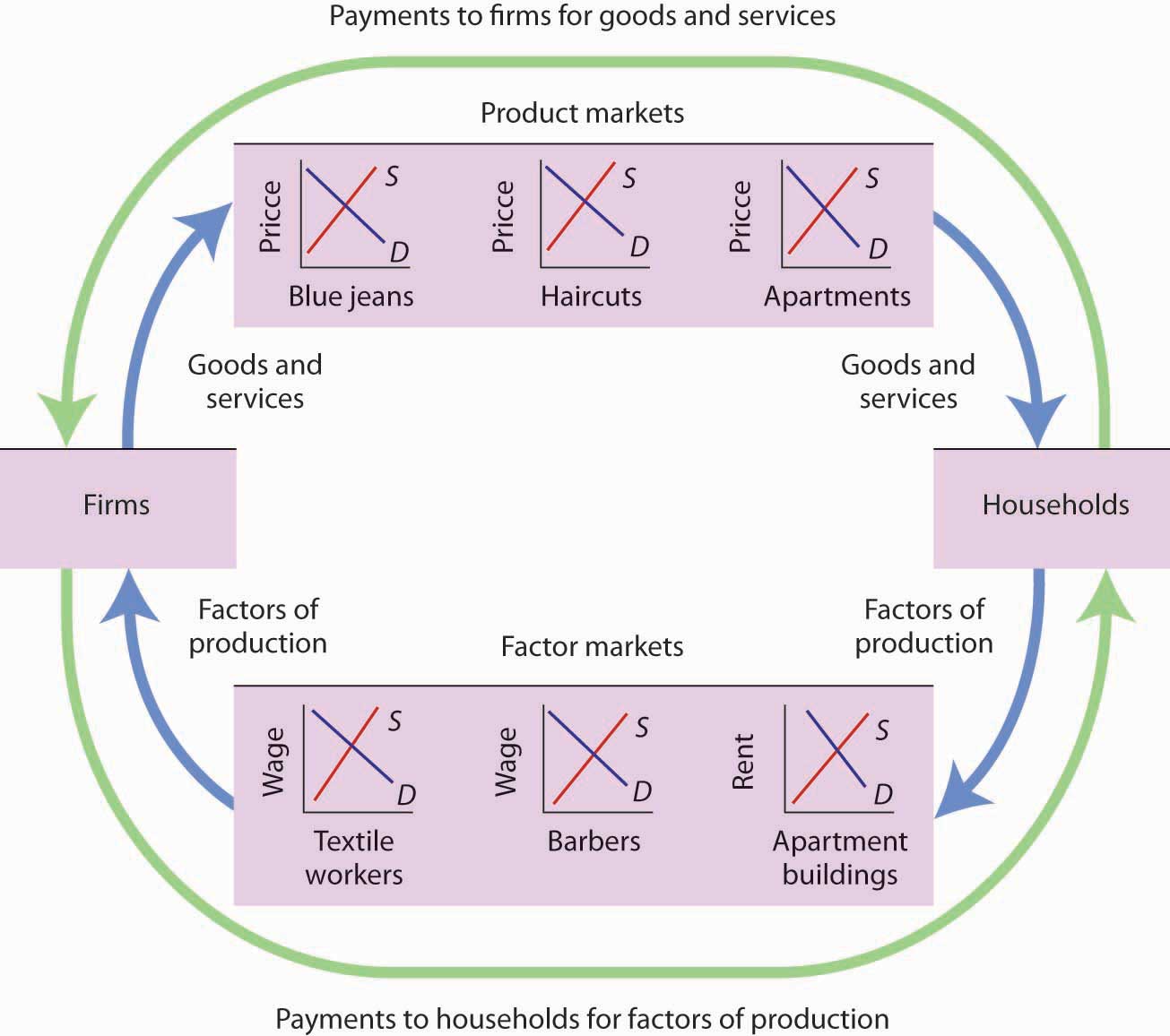

Implicit in the concepts of demand and supply is a constant interaction and adjustment that economists illustrate with the round flow model. The round flow model provides a look at how markets work and how they are related to each other. Information technology shows flows of spending and income through the economy.

A great deal of economic activeness can be thought of as a process of exchange betwixt households and firms. Firms supply goods and services to households. Households buy these goods and services from firms. Households supply factors of production—labor, capital, and natural resources—that firms require. The payments firms make in commutation for these factors correspond the incomes households earn.

The catamenia of goods and services, factors of product, and the payments they generate is illustrated in Figure ii.21 "The Circular Period of Economic Activity". This circular flow model of the economy shows the interaction of households and firms every bit they substitution goods and services and factors of product. For simplicity, the model here shows just the private domestic economic system; information technology omits the regime and strange sectors.

Figure 2.21 The Circular Flow of Economic Action

This simplified circular flow model shows flows of spending betwixt households and firms through product and factor markets. The inner arrows testify appurtenances and services flowing from firms to households and factors of production flowing from households to firms. The outer flows show the payments for appurtenances, services, and factors of production. These flows, in plow, represent millions of individual markets for products and factors of product.

The circular flow model shows that goods and services that households demand are supplied past firms in product markets. The exchange for goods and services is shown in the top half of Figure two.21 "The Circular Period of Economic Activity". The bottom half of the exhibit illustrates the exchanges that have place in cistron markets. factor markets are markets in which households supply factors of production—labor, upper-case letter, and natural resources—demanded past firms.

Our model is called a circular period model because households use the income they receive from their supply of factors of production to buy goods and services from firms. Firms, in turn, employ the payments they receive from households to pay for their factors of production.

The demand and supply model developed in this chapter gives usa a basic tool for understanding what is happening in each of these product or cistron markets and also allows usa to run into how these markets are interrelated. In Figure ii.21 "The Round Flow of Economic Activeness", markets for three goods and services that households want—blue jeans, haircuts, and apartments—create demands by firms for textile workers, barbers, and apartment buildings. The equilibrium of supply and demand in each market determines the price and quantity of that item. Moreover, a change in equilibrium in 1 market volition impact equilibrium in related markets. For instance, an increase in the demand for haircuts would pb to an increase in need for barbers. Equilibrium cost and quantity could rise in both markets. For some purposes, information technology will be adequate to merely look at a unmarried market, whereas at other times we will want to look at what happens in related markets besides.

In either case, the model of demand and supply is one of the about widely used tools of economic assay. That widespread use is no blow. The model yields results that are, in fact, broadly consistent with what we notice in the marketplace. Your mastery of this model will pay big dividends in your report of economics.

Key Takeaways

- The equilibrium toll is the toll at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. It is determined by the intersection of the need and supply curves.

- A surplus exists if the quantity of a good or service supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the electric current price; it causes downward pressure on price. A shortage exists if the quantity of a skilful or service demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at the current toll; it causes upward pressure on toll.

- An increase in demand, all other things unchanged, will crusade the equilibrium price to rise; quantity supplied will increase. A decrease in demand will cause the equilibrium price to fall; quantity supplied will decrease.

- An increase in supply, all other things unchanged, will crusade the equilibrium cost to autumn; quantity demanded will increment. A decrease in supply volition cause the equilibrium price to rising; quantity demanded will subtract.

- To determine what happens to equilibrium toll and equilibrium quantity when both the supply and demand curves shift, yous must know in which direction each of the curves shifts and the extent to which each curve shifts.

- The circular menstruum model provides an overview of need and supply in product and factor markets and suggests how these markets are linked to one another.

Try Information technology!

What happens to the equilibrium cost and the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals if the cost of film theater tickets increases and wages paid to DVD rental shop clerks increase, all other things unchanged? Be sure to show all possible scenarios, as was done in Effigy 3.19 "Simultaneous Decreases in Need and Supply". Again, you do not need actual numbers to arrive at an reply. Just focus on the general position of the curve(s) before and later events occurred.

Case in Indicate: Need, Supply, and Oil

As we all know – oil is an essential input used to produce gasoline, the price of oil is a key factor that determines gasoline prices. Indeed, as statistical data show, gas prices follow oil prices very closely. The importance of oil, however, expands far beyond that. In fact, oil is used to produce nigh everything, from heating and electricity generation to plastics, fertilizers, roofing, clothing, aspirin, and guitar strings. To satisfy the need for all those products, the earth produces near 100 million barrels (3.ii billion gallons) of oil per day. No wonder that fluctuations in oil prices touch on nearly all industries and may even modify the global macroeconomic situation. Because of such profound effects of oil prices on the global economy, information technology is important to examine the past trends in oil prices then that we could meliorate predict how they might change in the future. And oil prices do tend to fluctuate substantially. Have a look at Figure 2.22,

Figure 2.22 -Crude oil prices in 2012–2017

which shows how the "spot" prices of crude oil changed over the last five years. Particularly remarkable is the steep slump from about $112 per barrel to about $31 per barrel that occurred over the period from June 2014 to January 2016. Information technology is also worthy of notation that despite this 72% price drop, the consumption of oil during this catamenia increased rather modestly: from almost 94 million to about 96 million barrels per day, i.e. by only nearly 2%.ten What caused such a dramatic drop in the cost of oil accompanied by merely a slight increment in quantity? The demand and supply model discussed in this affiliate will help united states of america answer this question.

Let'south go through the four steps we've suggested in the previous section to assistance the states better organize our assay of events influencing the marketplace for oil. First, nosotros demand to define the marketplace we want to analyze. Since our purpose is to explain a trend in the world price of oil, not oil prices in detail countries or regions, it makes sense to examine the market for oil every bit a global market place.11 The suppliers in this global marketplace are all oil producers around the world, and the buyers are all earth's consumers of oil, which are predominantly businesses that apply oil to produce other goods.

Ane important question is whether the world market for oil fits our definition of a competitive market, i.due east. one where no individual seller or buyer tin influence the price. Recall that the ii conditions necessary for the buyers and seller to take the market cost as given are (1) the product is standardized, and (two) each buyer and seller holds a very pocket-sized fraction of the market, and then the influence of an individual heir-apparent or seller on the price is negligible. The first condition is certainly present, since crude oil is a standardized product (commodity). The second one does not strictly hold. The reason is that well-nigh twoscore% of the globe'due south crude oil is produced by the Arrangement of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which controls (or at least tries to) oil production in its member countries by setting production targets.

Because OPEC accounts for such a big share of the world's market for oil, it can affect its price. Historically, crude oil prices take risen when OPEC reduced its production targets. In our need and supply model, we tin can reverberate this OPEC'southward influence past shifting the world oil supply curve accordingly. However, OPEC'due south power to shift the world supply curve cannot change the police of supply. That is, when the price of oil rises due to OPEC'southward product cuts, other oil producers take the incentive to increment their output, since it becomes more than turn a profit-able to produce more oil even if it results in higher costs. Thus, we can employ the competitive demand and supply model to analyze the globe market for oil.

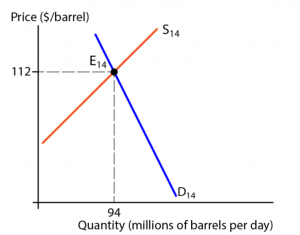

The second step is to define the initial market equilibrium. We volition commencement from June 2014, when the equilibrium price of oil was at its tiptop of almost $112 per barrel and its equilibrium quantity was about 94 million barrels per day.

In Effigy 2.23, D14 and S14 are, respectively, the demand curve and the supply curve in June 2014, and then point E14 marks the initial equilibrium. The 3rd step is to find the new equilibrium. Annotation, however, that our analysis hither is a trivial dissimilar from what we've done earlier: we al-ready know that in January 2016 the equilibrium price of oil was about $31 per barrel and the equilibrium quantity was almost 96 million barrels per mean solar day. What we need to figure out is which bend shifted in which direction, as we want to explain how the marketplace got at that place.

Figure 2.23 – The world marketplace for oil, June 2014

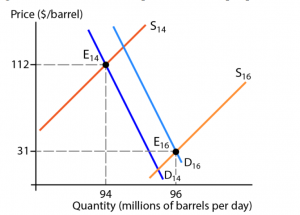

Let's start with the supply side. Well-nigh remarkable there is the phenomenal growth of oil production in the United States. The U.S. oil boom started in 2008, when the first well was drilled into a shale. Since so, with the assistance of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as fracking), billions of additional barrels of oil have been produced. Betwixt 2008 and 2015, U.S. oil production near doubled, reaching 9.4 one thousand thousand barrels per day and threatening to surpass Kingdom of saudi arabia as the world's largest producer of oil. In this situation, the OPEC countries faced a tough option: cut their oil production to prop up the toll, equally they've washed in the past, or maintain their output and let the price proceed to fall with the purpose of driving the producers of the more costly shale oil—in the U.s.a. and everywhere else—out of business. Quite surprisingly, OPEC, led by Kingdom of saudi arabia, decided not just to go with the latter pick, only increment their oil production substantially in the hope to win the global boxing for marketplace share. The U.S. shale oil producers, withal, did not back off. Armed with new drilling and other cost saving technologies, they connected to pump oil at well-nigh-record levels.

Figure 2.24 – The autumn in the price of oil explained

The result was a big rightward shift of the supply curve in the world market for oil as shown in Figure two.24, where S16 is the supply bend in January 2016. But what happened on the buyers' side of the market? Because, as we noted earlier, oil is used to produce about every product, the demand for it is largely driven by the demand for all those products, which increases when economies are growing. From this perspective, although the global demand for oil increased, driven mainly past continuing economic growth in India and China, the increase was rather pocket-sized. China's growth was shaky, and in Europe and the U.s. the annual rates of growth were beneath 3%. Thus, although the world's demand curve for oil shifted rightward (from D14 to D16 in Figure ii.24), the effect of the need shift was much smaller than that of the supply shift.

As you tin can encounter in Figure 2.24, since the downward effect on the price of the increased supply was much greater than the upward effect on it of the increased demand, the toll dropped dramatically, from $112 per barrel in the June 2014 equilibrium (E14) to $31 per barrel in the January 2016 equilibrium (E16).

You might be wondering, however, why such a substantial drop in the price of oil resulted in simply a relatively small increment in its quantity. Given that the rightward shifts of both supply and demand curves worked in the same direction, reinforcing each other to increment the equilibrium quantity, wouldn't nosotros expect a much greater quantity increase? The respond to the this question is that, first, the shift in the demand curve was rather small. 2nd, along the new same demand curve (D16) the responsiveness of the quantity of oil demanded to a change in price was very small. Economists phone call information technology a very price inelastic demand. We discuss the economic concept of the price elasticity of demand and the reasons why the need for oil is very price inelastic in Chapter 3.

Source: Ogloblin, Constantin; Dark-brown, John; King, John; and Levernier, William, "Microeconomics for Business" (2018).Business Administration, Management, and Economics Open Textbooks. 6.

Answer to Try Information technology! Problem

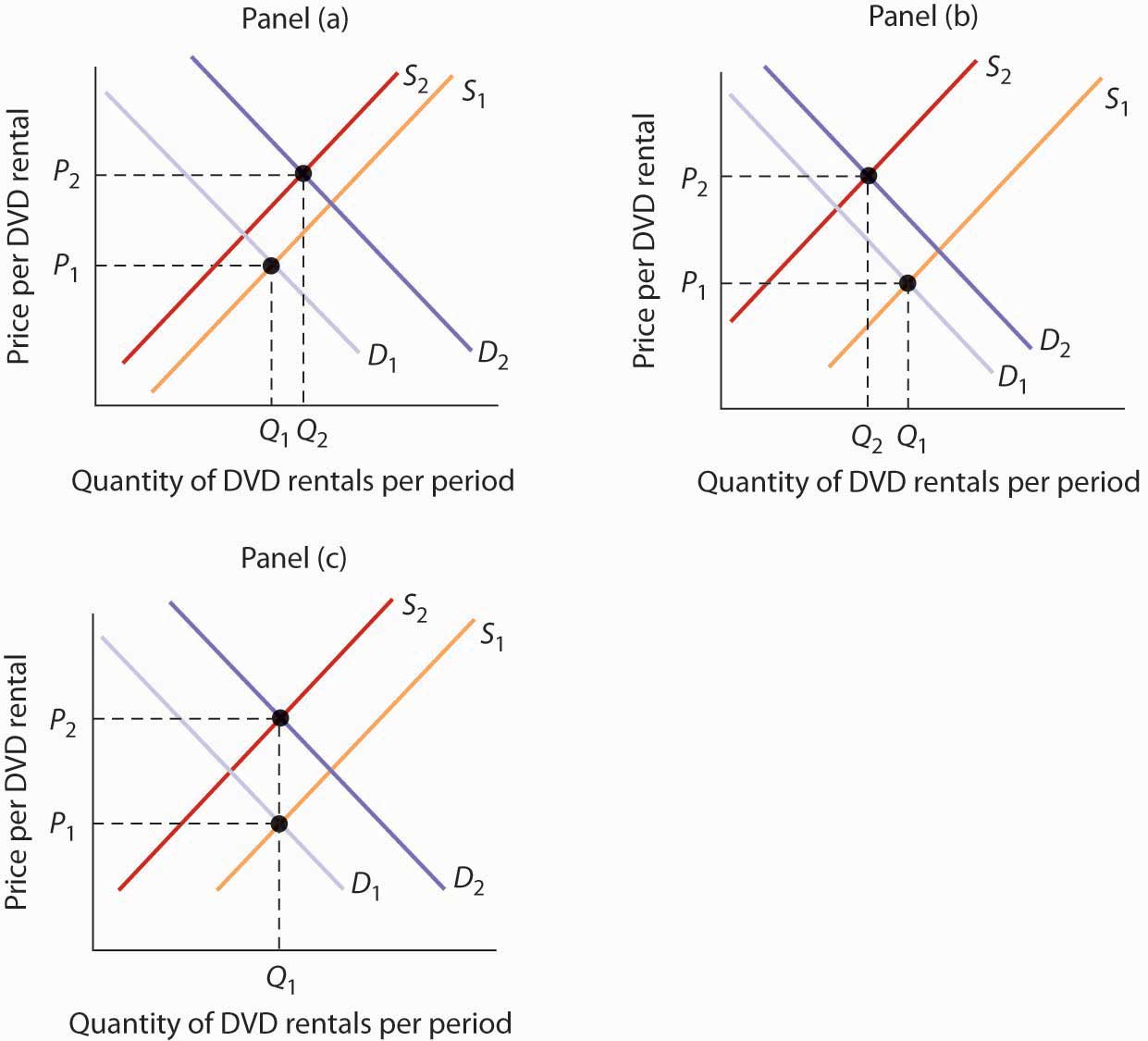

An increment in the toll of movie theater tickets (a substitute for DVD rentals) volition cause the demand curve for DVD rentals to shift to the right. An increase in the wages paid to DVD rental store clerks (an increment in the cost of a factor of product) shifts the supply bend to the left. Each result taken separately causes equilibrium price to rising. Whether equilibrium quantity will exist college or lower depends on which bend shifted more.

If the demand curve shifted more, so the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals volition rise [Console (a)].

If the supply curve shifted more, and so the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals will fall [Panel (b)].

If the curves shifted by the same amount, and then the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals would not change [Console (c)].

Figure two.25

Which Are Needed To Determine The Equilibrium Of A Good Or Service,

Source: https://uw.pressbooks.pub/microman/chapter/2-3-demand-supply-and-equilibrium/

Posted by: stewartmadid1958.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Are Needed To Determine The Equilibrium Of A Good Or Service"

Post a Comment